Is there an AI bubble? OBVIOUSLY. Is that a bad thing? Inquiring minds want to know.

I recently read “The Hater’s Guide To The AI Bubble” by Ed Zitron and while he shares a LOT of anecdotal insights, I think he’s missing crucial historical context that changes how we should interpret these developments.

Why? Well, for a few reasons…

It’s NOT that I think he is wrong per se, or that I believe everything that the AI hypesters are saying, or that I don’t think we should listen to critics, or anything along those lines.

It’s more about the misplaced hyperbole, and the bigger picture that he could easily be missing. A “forest for the trees” problem of perspective and scale. Are there some trees on fire? Sure. Maybe a decent amount of them. Is the entire global forest going to burn because of it?

While I acknowledge the risks of any market correction, the historical pattern suggests this is more likely to be a necessary transition than an economic catastrophe. The infrastructure being built during these ‘wasteful’ periods typically becomes the foundation for the next growth phase.

I could dive deeper into the financial modeling of what a correction might look like, but I’ll leave the detailed analysis to the financial experts and focus on the technological and historical patterns instead.

The Historical Pattern: Bubbles Are Features, Not Bugs

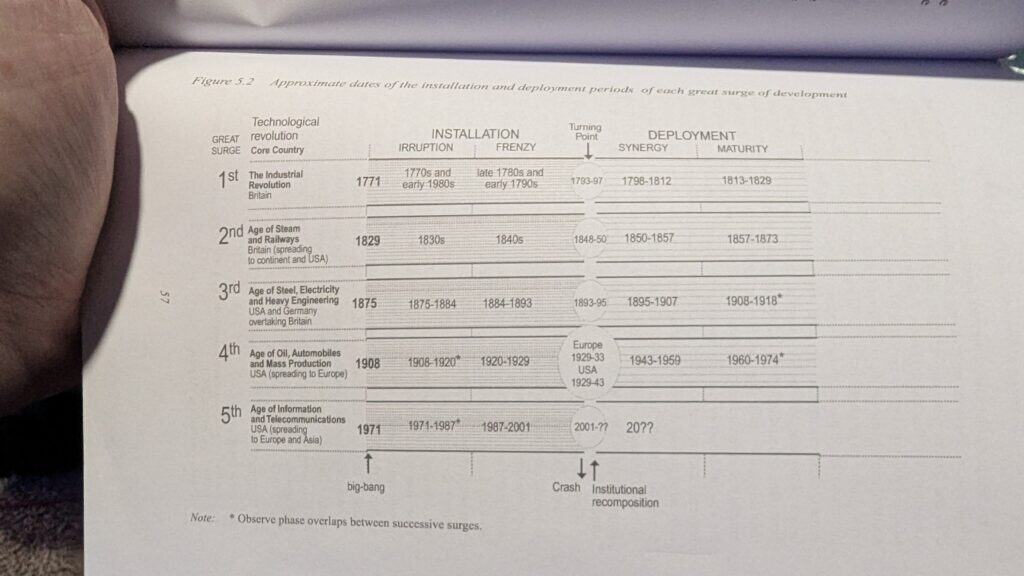

Along those lines, I’d like to show you something you may not have seen before. The charts that accompany this post are from Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital by Carlota Perez. It’s a fantastic book and if you have any interest in either technology, finance, history, or the future 😎 I recommend you read it!

Here’s the main takeaway: Every single technological revolution has created a bubble, and then a crash, and only then an institutional recomposition that ultimately unleashes the full economic benefits of a new technological paradigm. As you can see from the timeline below, this has already happened FIVE times, like clockwork, and so my money is on it happening again.

This is where Ed’s analysis goes astray; he’s treating the current AI frenzy as if it exists in a historical vacuum, when in fact we’re likely witnessing the final bubble phase of the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) revolution that began in the 1970s. According to Perez’s framework, we’re still in the turning point phase of the ICT revolution; we’ve had multiple frenzies (dot-com, housing/2008, and now AI) but haven’t yet reached the golden age of full deployment.

What’s particularly interesting about Perez’s framework is that it suggests the AI bubble critics are actually validating that we’re on the right track. In previous revolutions, the critics who pointed to “wasteful spending” on canals, railways, and fiber optic cables were technically correct about the waste, but completely wrong about the long-term significance.

Why Infrastructure Overspend Is Actually Necessary

This is crucial context that Ed misses, and it’s where his argument about AI “not being infrastructure” falls apart. Having worked in networking and telecom for 20 years, I’ve seen firsthand how infrastructure build-outs work. The “over-investment” in fiber during the dot-com era that everyone called wasteful? That dark fiber became the backbone of our current internet economy. The pattern Perez describes isn’t just theoretical; it’s how critical infrastructure actually gets built.

Ed argues that AI isn’t infrastructure like previous technological revolutions, but this misses how our definition of infrastructure constantly evolves. The steam revolution built physical railways and canals. The electricity revolution built power grids. The ICT revolution is building digital infrastructure. And yes, massive data centers full of GPUs and SSDs absolutely qualify as infrastructure.

These “AI factories” that NVIDIA promotes aren’t just marketing speak; they’re the digital equivalent of the steel mills, power plants, and rail yards of previous eras. When Microsoft spends $80 billion on data centers, or when Amazon builds massive server farms, they’re playing the same role that private railroad companies, steel manufacturers, and oil refineries played in previous revolutions. The infrastructure is private sector-led, but it’s infrastructure nonetheless.

From a network architecture perspective, what we’re seeing with AI infrastructure resembles the early internet build-out. Lots of redundant capacity and seemingly wasteful parallel efforts that will eventually interconnect in ways we can’t fully predict. The waste that critics love to point out isn’t evidence that the technology is worthless; it’s evidence that we’re in the messy, expensive phase where the digital infrastructure gets built.

Consider the historical precedent: the railroad bubble of the 1840s was catastrophic for investors but built the track infrastructure that enabled the western expansion and industrial growth of the late 1800s. The electricity bubble of the 1890s crashed spectacularly but created the power grid that enabled the mass production era. Yes, a lot of money will be lost. Yes, many companies will fail. But the data centers will be built, the GPU clusters will be installed, and the digital infrastructure will be ready for whatever comes next.

Why We Know The Golden Age Hasn’t Started Yet

So how do we know we haven’t reached the golden age of the ICT revolution? Perez is quite explicit about this. She notes that “even after 40 years, the information and communications technology (ICT) revolution is far from complete. It hasn’t fully changed our way of life, as previous technological revolutions had done.”

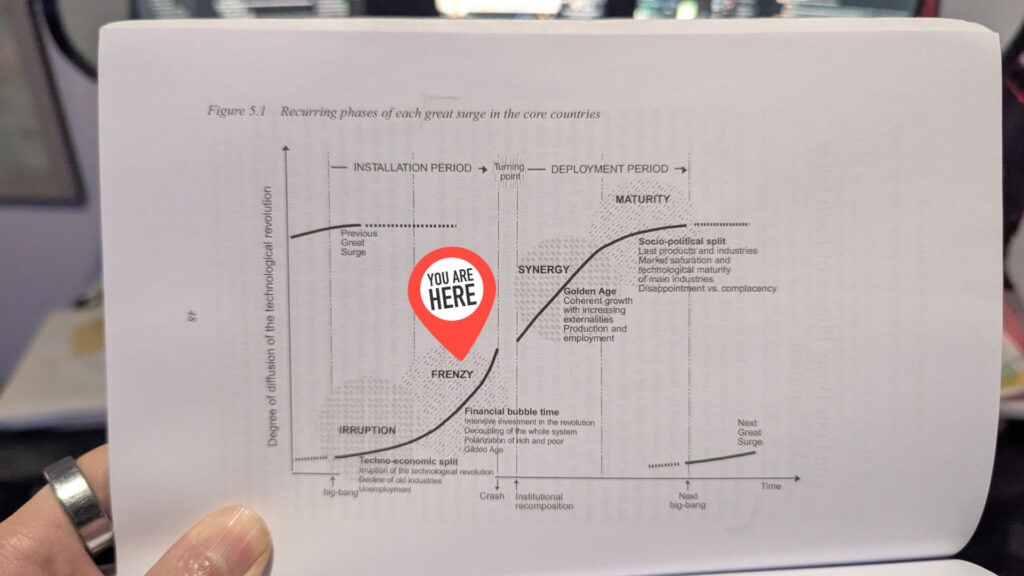

What would an ICT golden age actually look like? According to Perez, it requires “smart, green, fair and global growth.” A fundamental reorientation of how we use digital technology to solve global challenges. The diagram below shows where we likely are in the current cycle. Still in the messy transition phase, not yet in the “Golden Age” of coherent growth and broad prosperity.

Compare this to what previous golden ages looked like: the post-WWII boom brought suburbanization, mass prosperity, and fundamental changes in how people lived and worked. Perez points to historical examples like “the Victorian boom, the Belle Epoque and the Post War prosperity” as genuine golden ages where technology transformed entire societies.

She argues that “to turn the corner from crisis to golden age would require a major economic and political consensus: an intelligent global policy framework giving a convergent direction to investment and innovation.”

We’re clearly not there yet. The current period shows “a dangerous political shift, the separation of the interests of major global corporations from interests of the national societies where they are based.” Instead of technology serving broad human flourishing, we have increasing inequality, political polarization, and environmental destruction. All signs that we’re still in the messy transition phase.

As Perez herself said in 2019: “I see the present as the 1930s, the turning point of the IT surge. We have had 2 frenzies and we have not yet had a golden age.” The AI bubble may very well be the final frenzy that pushes us toward that long-awaited transformation.

The LLM vs. AI Confusion

Now, there’s another flaw in Ed’s analysis that compounds this historical blindness: he purports to be talking about AI broadly, but he’s actually focused almost exclusively on LLMs and generative AI on the product side. This is like analyzing the internet revolution by only looking at pets.com while ignoring the broader infrastructure transformation happening underneath.

Just as we had format wars (VHS vs. Beta) and protocol battles (TCP/IP vs. OSI) in previous revolutions, the current AI “waste” includes the market working out which approaches will become standard. This apparent inefficiency is actually the market’s way of exploring the solution space.

AI (in the broader sense of machine learning, computer vision, robotics, and yes, language models) represents the mature deployment of the ICT revolution. Companies have been investing in these technologies for decades, long before ChatGPT caught the zeitgeist in 2023. What we’re seeing now isn’t the birth of a new revolution, but the final flowering of the digital revolution that started with the microprocessor.

The current AI bubble may very well be the catalyst that finally pushes us into the golden age that Perez’s framework predicts should follow the ICT revolution. After the inevitable crash and institutional rebalancing, we’ll likely see the real deployment of machine intelligence across society. Not as flashy consumer products, but as the invisible infrastructure that makes everything work better.

What About the Next Revolution?

But what about the NEXT revolution? That’s where things get interesting. It might be biotechnology and gene editing like CRISPR. It might be quantum computing, which could create a bubble that makes today’s AI spending look quaint. It might be nanotechnology or fusion energy or something we haven’t even imagined yet. But according to both Perez’s historical analysis and her current thinking, it’s probably not AI. AI is the culmination of the current revolution, not the beginning of the next one.

The Bottom Line

As someone who’s built a career understanding how network technologies evolve and scale, I’m less concerned about the bubble and more interested in which infrastructure investments will prove foundational for the next phase. The question isn’t whether there’s waste. There always is. The question is whether we’re building the groundwork for the next era of technological development. And from what I see, it is very possible we are; even though we still don’t know exactly what that looks like.

In other words, the waste Ed documents isn’t a bug in the system. It’s a feature of how technological revolutions actually unfold. And if history is any guide, the real benefits are still to come.